Why corporate waffle always feels fake to Gen X: An autopsy of professional jargon

Gen Z takes on why Gen X always hated corporate bullshit

There is a particular phrase that still echoes through certain corridors of British business. It is usually delivered in a tone of strained optimism. “We need to think outside the box on this one.” When I hear it now, in a Teams call or a strategy doc, it sounds less like an instruction and more like a relic. It is a shard of a dialect my generation never properly learned, a code from a different war. To us, the much-mythologised cynicism of Generation X can sometimes appear as a simple personality trait, the cultural legacy of grunge and a few too many viewings of Fight Club. But that is a superficial reading. Look closer, and what seems like disengagement reveals itself as something more principled. It was not cynicism for its own sake. It was a rational, linguistic survival strategy, forged in the specific economic fires of their coming of age.

A Generation of Their Own

For Gen X, entering the workforce in the late 1980s and 1990s, the social contract was being rewritten in real time. The post-war promise of a job for life, a final salary pension, and linear progression evaporated. In its place came what Douglas Coupland, in his defining novel Generation X, termed the 'McJob'. This was not merely a poor job. It was 'a low-pay, low-prestige, low-dignity, low-benefit, no-future job in the service sector.' The statistics bore out the mood. The shift from defined-benefit to defined-contribution pensions transferred risk from institution to individual, a quiet financial revolution that underscored a broader message. You were on your own.

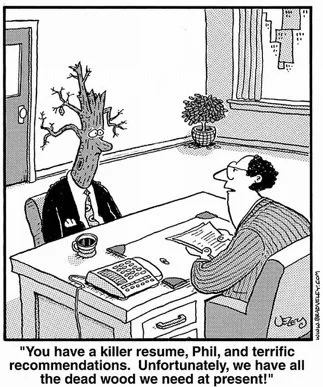

Into this instability marched a new language. It spoke not of security, but of constant, fluid reinvention. 'Downsizing' softened the brutality of redundancies. 'Rightsizing' made it sound like a geometric necessity rather than a human cost. This was more than jargon. In organisational theory, this is known as 'strategic ambiguity', language deliberately flexible to allow for multiple interpretations and managerial deniability. For a manager, it was a tool. For a Gen X employee, it was a weapon turned against them. Phrases like 'leveraging synergies' or 'paradigm shifts' created a semantic fog. Within it, the concrete realities of job security and fair compensation could be obscured, rebranded as mere challenges on a journey of growth. To internalise this language was to internalise the lie. Their refusal to do so was not petulance. It was an act of ethical resistance.

British culture of the time offered no refuge from this dissonance, only amplification. While American films like American Psycho depicted corporate life as a shell for psychosis, the British iteration was a quieter, more familiar despair. It was the soul-crushing inertia of The Office, Ricky Gervais's David Brent desperately cloaking his inadequacy in a quilt of mangled management speak. It was the lyrics of bands like Radiohead, giving voice to a numb, modern alienation in tracks like 'Fitter Happier'. Even the defiant, anti-establishment rage of a band like Rage Against the Machine, while American, soundtracked a universal feeling. The system was not just unfair. It was speaking in bad faith.

Our Turn, Our Tools

My generation, Gen Z, inherited a different landscape but the same fundamental suspicion. We did not experience the shock of the pension shift. We were born into its precarious aftermath. The gig economy is our baseline. Our medium for dissent, however, is profoundly different. The Gen X response was often the silent eyeroll, the internal exit, the subversive compliance captured in Dilbert. Where Dilbert comics succeeded as a medium in the 90s, Gen Z now relates to similar relatable frustrations through TikTok and Instagram shit posts. Social media has allowed a new generation to come online and openly vent frustrations with specific workplaces, cultures and even specific employees or employers, making fear of cancellation or public backlash a lot more palpable. Where Gen X developed a refined, internal cynicism, we practice open-source semiotic analysis. The impulse is shared. The execution is networked.

Building a Language of Substance

This is not to say our way is superior. It is simply different, a product of our tools. The lesson for the future of work is not to abandon structure or professional language. The lesson is to rebuild a lexicon of work that means what it says. We must demand that language regains a concrete, accountable relationship with reality. To speak of 'wellbeing' while monitoring keystrokes is to repeat the old sins. To discuss 'sustainability' without transparent supply chains is to thicken the fog.

The Gen X project was a necessary refusal. They saw the code for what it was, a shield for power, and chose not to learn it fluently. Our project, building upon theirs, must be to write a new one. One where clarity is valued over cleverness, where concrete action precedes aspirational statement, and where the words spoken in a boardroom bear a recognisable resemblance to the experience on the shop floor, or in the home office. Their battle was to see through the nonsense. Ours is to build something in the space they cleared.

Aoife Grimes, 25, corporate Gen Z

Written for Moo Marketing Copy