Why does AI write like that? AI writing and its effects on the marketing industry.

You have likely read its work already today. A product description that feels airless, a brand newsletter that rings a faint, tinny bell of familiarity. Its prose is smooth, competent, and curiously flat. This is the sound of AI writing. It is not poor writing in a traditional sense. It is something else, a new dialect. This dialect is becoming the background noise of the modern marketing industry, and its implications run deeper than efficiency.

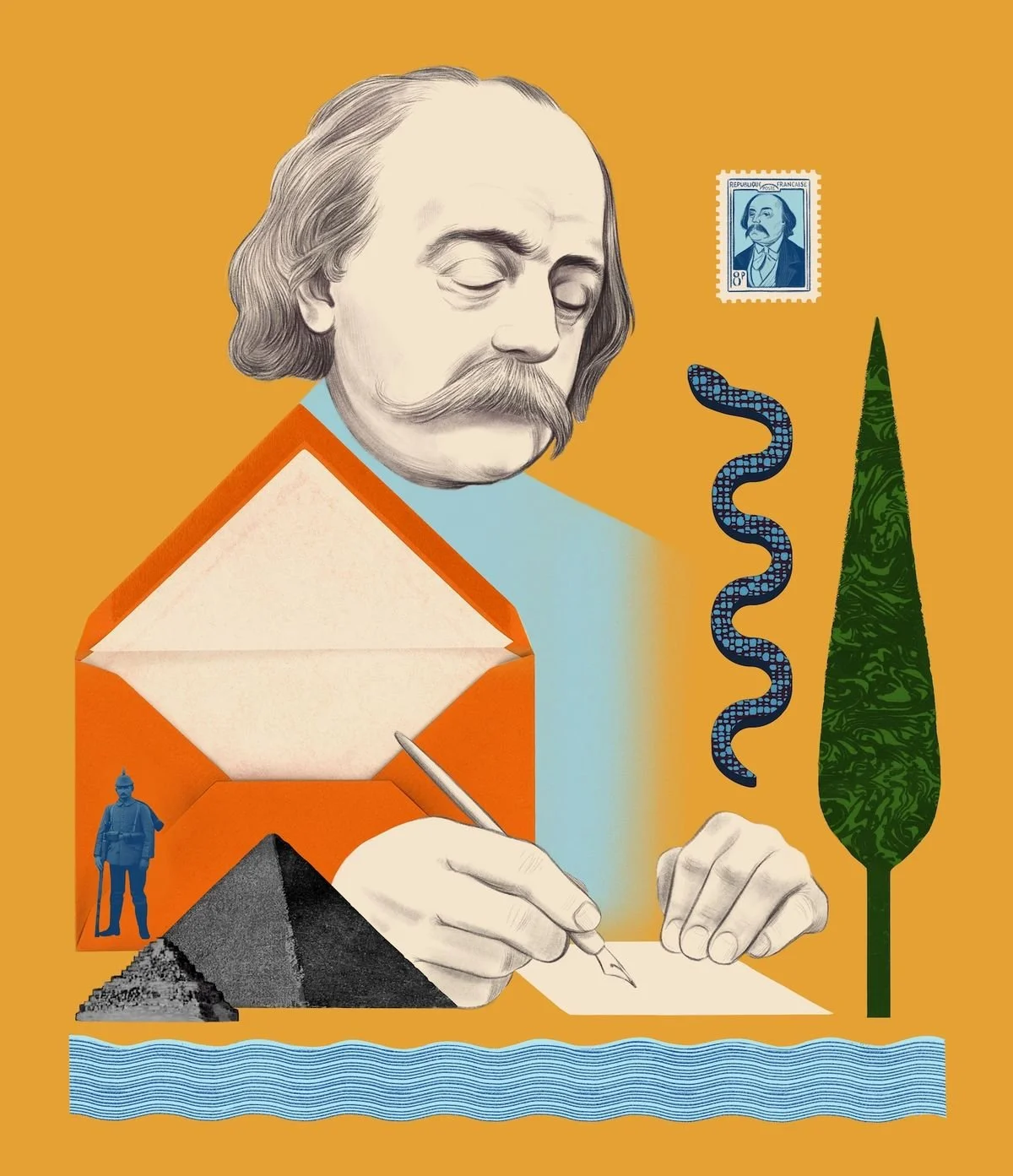

The oddness is inherent. A large language model is trained on a staggering volume of our most common words. It learns probability, not meaning. It masters pattern, not purpose. Therefore, its voice is not a voice at all. It is an average. It is the linguistic mean of countless blog posts, annual reports, and website copy. The French novelist Gustave Flaubert famously tortured himself searching for le mot juste, the single exact word. The AI operates on a different principle. It selects le mot probable, the most statistically likely word. The result is a text without a source, a message without a messenger. It has the shape of communication but not the heat.

This synthetic output finds a perfect antithesis in literature’s celebration of the messy self. Consider the narrator of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground. He is spiteful, illogical, and vibrantly human. His voice is a weapon against a world demanding rational, polished conformity. An AI could never generate his chaotic brilliance. It could only produce a clinical summary of his condition. The former is art. The latter is an annotation. This distinction matters profoundly for marketing; a field built on connection. We connect to voices, not to summaries.

Why then does this average voice proliferate across agencies and content plans? The driver is often pressure, not indolence. Research from the Stanford Institute for Human-Centred AI indicates most professionals now use these tools to manage overwhelming content demands and to bypass the paralysis of a blank page. The tool offers a lifeline in a sector obsessed with scale and speed. I recall using one during an internship to parse complex financial briefs I did not fully grasp. It created a simulacrum of understanding, a facade of competence. The ethical unease begins here, not with the use itself, but with the conditions that make it indispensable. When the metric is volume, the average becomes the standard.

Two quiet costs follow this adoption. First, a narrowing of discovery. When we ask an AI to summarise, we accept its algorithmic curation of sources. It reinforces the dominant narrative, the already popular idea. It does not stumble upon the obscure reference, the contradictory study, the niche perspective that sparks true innovation. Our research becomes a closed loop, polished and insular. Second, and more critical for marketing, is a trust deficit. Data from a 2024 Tessian report shows most UK consumers instinctively distrust brand communications that feel generically automated. The audience senses the void. We are wired to seek the fingerprint of human thought, the slight imperfection that signals authenticity. Its absence triggers disengagement, not delight.

The central question is therefore not whether the writing is good. It is about what we surrender in the process. Language is not merely a vessel for thought. The struggle to shape a sentence is the struggle to shape the idea itself. To outsource this compositional act is to outsource a part of thinking. Can a process designed to reassemble existing fragments ever produce a genuine new whole? The form is not just the container. It is the thought.

This synthetic average is already altering our landscape. A study published in Science noted a detectable shift towards homogenised language in scientific and marketing preprints, a subtle erosion of lexical diversity. The accent is spreading.

Yet a stubborn human preference remains. Observe the recent public reaction to two campaigns. Coca Cola's "Masterpiece" advertisement, a spectacle of AI generated imagery, was met with global apathy. It was a technical feat that resonated as a cold trick. Contrast this with the warmth generated by Apple’s "Underdogs" commercial for the Macintosh, which celebrated tangible, hands on creation with practical effects. The audience did not just see the ad. They felt it. One was manufactured. The other was made.

The future path is not to reject the tool but to define its role with precision. Let this synthetic voice handle the genuinely repetitive, the data driven update, the first draft of the generic. But we must consciously, even fiercely, reserve the spaces that matter for the human voice. The brand story that builds a legacy, the creative concept that requires a leap, the copy that needs a soul, these are not tasks for the average. They are tasks for a person. The goal is not to make the machine sound more like us. It is to use its capabilities to free us to do what it cannot. People do not crave flawless perfection. They crave the authentic spark of another mind. And that, for now, remains a uniquely human offering.