The Ugliest Thing That Survives. Why Hope is the Real Work of Words

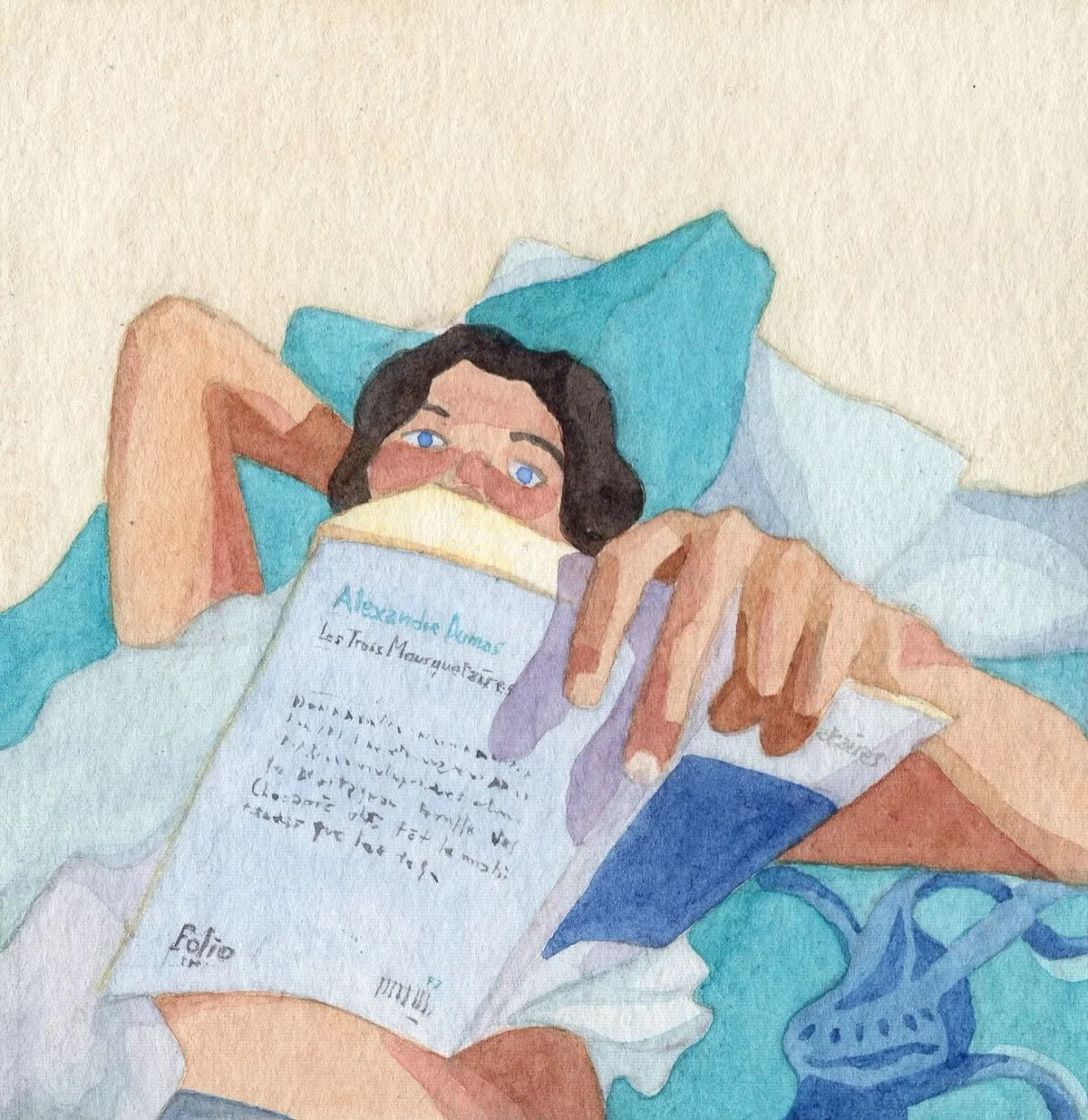

© Jean Aubertin

Faith in grand narratives feels increasingly difficult to justify. We open the news to another cache of Epstein documents. We watch comedians we admired perform in Riyadh, smiling before a regime implicated in a journalist’s murder. The institutions we were told to trust seem less like pillars and more like painted scenery. It is all cracking. Cynicism becomes the rational response, a safe layer against disappointment. Yet beneath that brittle surface something else persists. It is not optimism. Optimism is passive, a sunny guess about tomorrow. What I mean is far less polite. The poet Caitlin Seida called it a sewer rat. Hope is the ugly thing with teeth and claws and patchy fur that has seen some shit. It thrives in the discards. It survives in the darkest places when nothing else can even find a way in. This tenacious and unglamorous hope is not merely a feeling. It is the most potent and contested material in the craft of language itself.

To understand its power look to where hope is engineered. Consider the copywriter’s text. Often dismissed as commercial fluff, professional persuasion is ultimately the architecture of believable futures. The mechanism is simple and profound. Identify a latent yearning for security or status or transformation. Then construct a linguistic bridge to its fulfilment. This is not so different from the work of nation-building. Twentieth century American propaganda did not sell policy. It sold the American Dream. This was a narrative of individual hope so potent it could motivate generations and morally underwrite immense power abroad. The promise was not of a state but of a personal destiny.

Contemporary China employs a parallel linguistic strategy. Slogans like the Chinese Dream or ‘common prosperity’ "共同富裕" are masterclasses in branded collectivism. Launched as a central policy framework around 2021, this term is far more than an economic directive. It functions as a masterful piece of copywriting, designed to manufacture and direct public hope. The slogan implicitly acknowledges the social anxiety and inequality generated by decades of rapid growth ("the painful now"). It then posits a collective, state-guided future where these disparities are resolved ("the redeemed later").They are not political statements so much as marketing campaigns for a national future. They skilfully align personal aspiration with state stability. The tool is hope, meticulously packaged and distributed. In both cases the objective is influence. The currency is a vision of a better tomorrow. The most effective language offers a credible path from a painful now to a redeemed later.

The true ingenuity of such systems lies in their ability to co-opt the very desire for change. Observe how certain political dialects employ religious framing in modern America. The language of spiritual warfare, of battling devils in high places, channels legitimate outrage into a narrative with a built-in resolution. Prayer and personal piety. The hope for structural change is subtly redirected into a hope for individual salvation. This becomes a form of devotional self-surveillance demanding obedience over action. It is a devastatingly effective piece of rhetorical jujitsu. It offers the solace of hope while neutering its disruptive potential.

This reveals hope’s complex nature. We mistake it for the buoyant optimism of the victor. Its most powerful form is born in the acknowledgement of defeat. In his 1967 sermon Shattered Dreams, Dr Martin Luther King Jr confronted this agony directly. He spoke of the crushing weight of fighting for what is demonstrably right. Of having moral and even divine alignment and still failing. Sometimes you lose, he acknowledged. The hope that follows such a realisation is not bright. It is the decision to continue when every observable metric suggests surrender is the only logical course. It is the sewer rat’s resolve, not the bird’s flight.

This is why the spectacle of comedians performing in Riyadh resonated as a profound betrayal. The issue transcended comedy or foreign engagement. It represented the abandonment of a specific and fragile hope. The hope that those gifted with a public platform might privilege a consistent humanity over transactional opportunity. It was a trade of the gritty principled rat for a gilded cage. A confirmation that even our perceived iconoclasts bow to the oldest corruptions. It felt like the shattering of a smaller but deeply held dream.

So what becomes of our words when the grand narratives fail. This moment of disillusion is not hopelessness. It is the necessary ground for a more honest kind of hope. The prepackaged glossy version has expired. What remains is the resilient ugly thing. Our task with language now is not to rebuild the polished stage sets. We must learn to speak credibly from the rubble. This means forging a different rhetoric. One that trades the hollow grandeur of the greatest nation for the quiet dignity of a practical solution. A brand voice that bears the texture of its scars. A story that values the integrity of a long losing fight as much as the easy victory.

People often think fear is the great motivator. It is not. Fear paralyses. It is the agent of the doom-scroll, the generator of inert despair. What compels action, even trembling action, is its counterpart. The slim defiant hope that the world as it is need not be the world as it will be. We move through fear because of hope. They are not opposites but essential partners in any struggle worth the name.

The powerful will always attempt to author our hopes for us. They sell futures that consolidate their position. The ultimate act of linguistic resistance is therefore to write our own. To wield words not as a sedative but as a tool for truthful construction amidst the ruins. To craft narratives that honour the struggle more than the trophy. This is the real work left to us. Not to mimic the soaring empty proclamations of a broken past. But to become, with clear eyes and steady hands, scribes for the stubborn surviving rat. Its hope is not much. But it has teeth. And it is, irrevocably, ours.

Aoife Grimes, 25 year old Corporate Gen Z